Top 10 Muslim Inventions

As Salaam Alaikum Halal travellers, Islamic scholars have made significant and lasting contributions to various fields of knowledge, such as mathematics, astronomy, medicine, philosophy, and art. They preserved and transmitted the classical heritage of ancient civilizations and enriched it with their original insights and discoveries. They also fostered a culture of learning and intellectual curiosity across the Islamic world and beyond. Their achievements deserve to be respected and celebrated by all who value human civilization and progress.

In the medieval period, Muslims made significant strides in the evolution of modern sciences. They were theoretical scientists, thinkers, and inventors of numerous beneficial devices. Despite the constraints of their era, their accomplishments were substantial. They pioneered an experimental method that supplanted the Greek speculative method and later became the cornerstone of all scientific investigations.

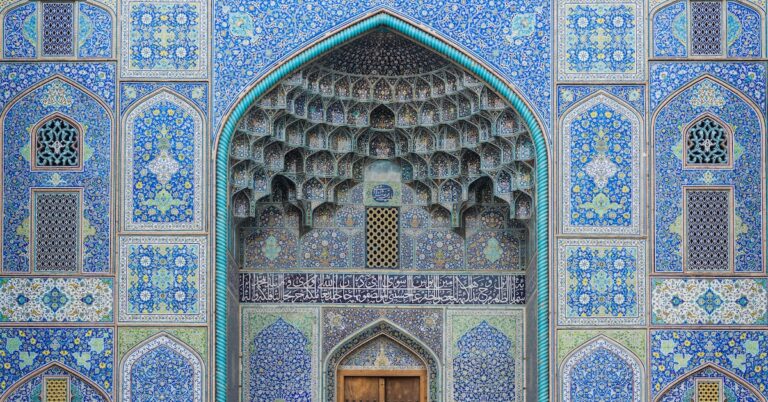

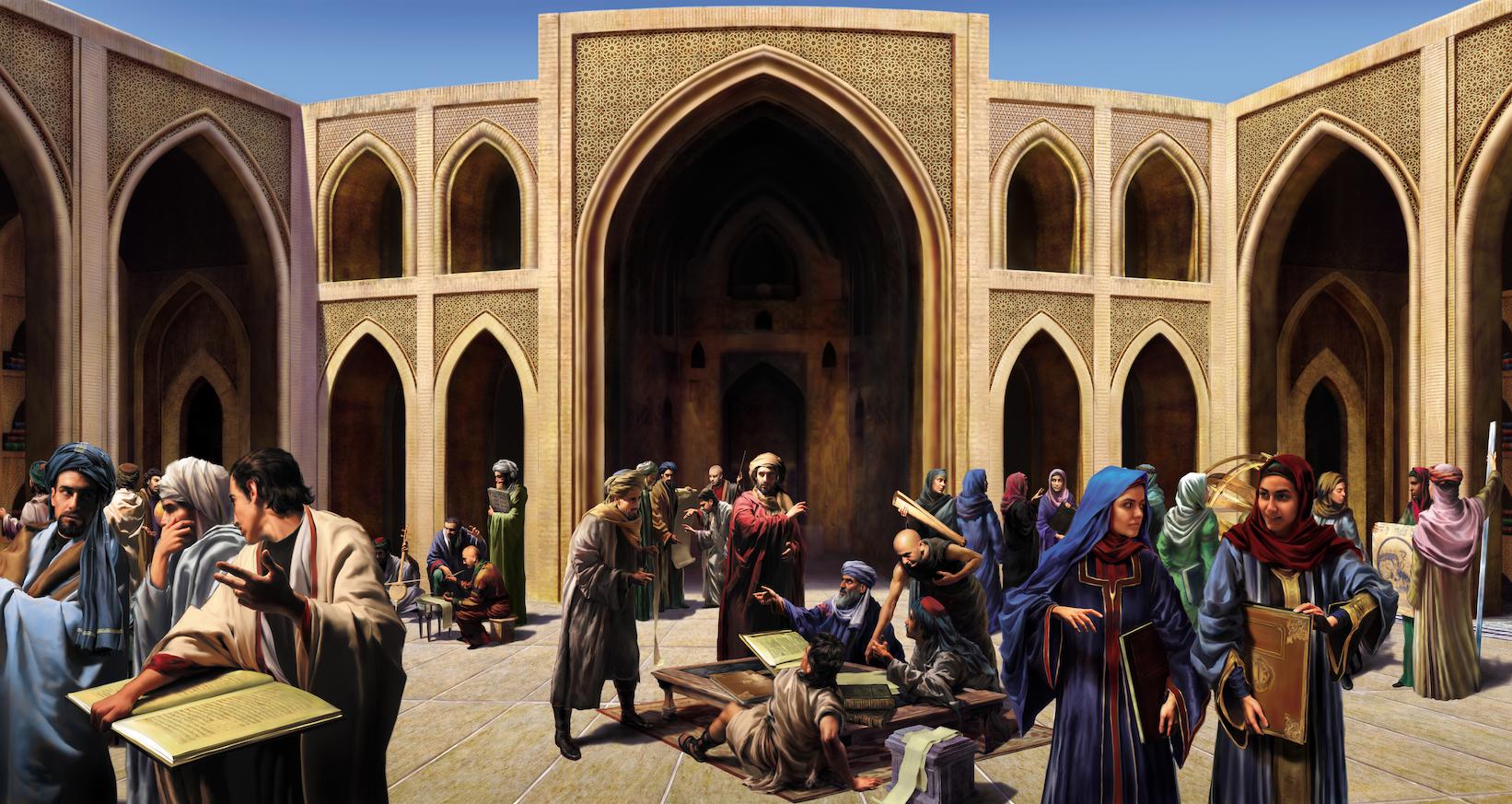

While Medieval Europe was in decline and darkness, the Islamic world was experiencing a Golden Age under the Abbasid caliphate, marked by significant cultural, economic, and scientific advancements. The House of Wisdom in Baghdad was the cradle for numerous scientific and technological innovations unseen since the ancient Greeks. The Islamic Empire, surpassing even the Roman Empire in its prime in terms of size, dedicated considerable effort and resources to advancing science and technology. This had a profound and lasting impact on science and all facets of life.

Indeed, in the creation of the heavens and the earth and the alternation of the day and night there are signs for people of reason.

˹They are˺ those who remember Allah while standing, sitting, and lying on their sides, and reflect on the creation of the heavens and the earth ˹and pray˺, “Our Lord! You have not created ˹all of˺ this without purpose. Glory be to You! Protect us from the torment of the Fire.

إِنَّ فِى خَلْقِ ٱلسَّمَـٰوَٰتِ وَٱلْأَرْضِ وَٱخْتِلَـٰفِ ٱلَّيْلِ وَٱلنَّهَارِ لَـَٔايَـٰتٍۢ لِّأُو۟لِى ٱلْأَلْبَـٰبِ

ٱلَّذِينَ يَذْكُرُونَ ٱللَّهَ قِيَـٰمًۭا وَقُعُودًۭا وَعَلَىٰ جُنُوبِهِمْ وَيَتَفَكَّرُونَ فِى خَلْقِ ٱلسَّمَـٰوَٰتِ وَٱلْأَرْضِ رَبَّنَا مَا خَلَقْتَ هَـٰذَا بَـٰطِلًۭا سُبْحَـٰنَكَ فَقِنَا عَذَابَ ٱلنَّارِ

Quran Al-i-Imran 3:190-191

There are certain people whom Allāh chooses from amongst the masses to give them blessings so that they can assist others. Allāh will keep such blessings with them so long as they continue using them to assist others. However, if they stop doing so, it is taken away from them and given to somebody else.

The Prophet Muhammed (PBUH)

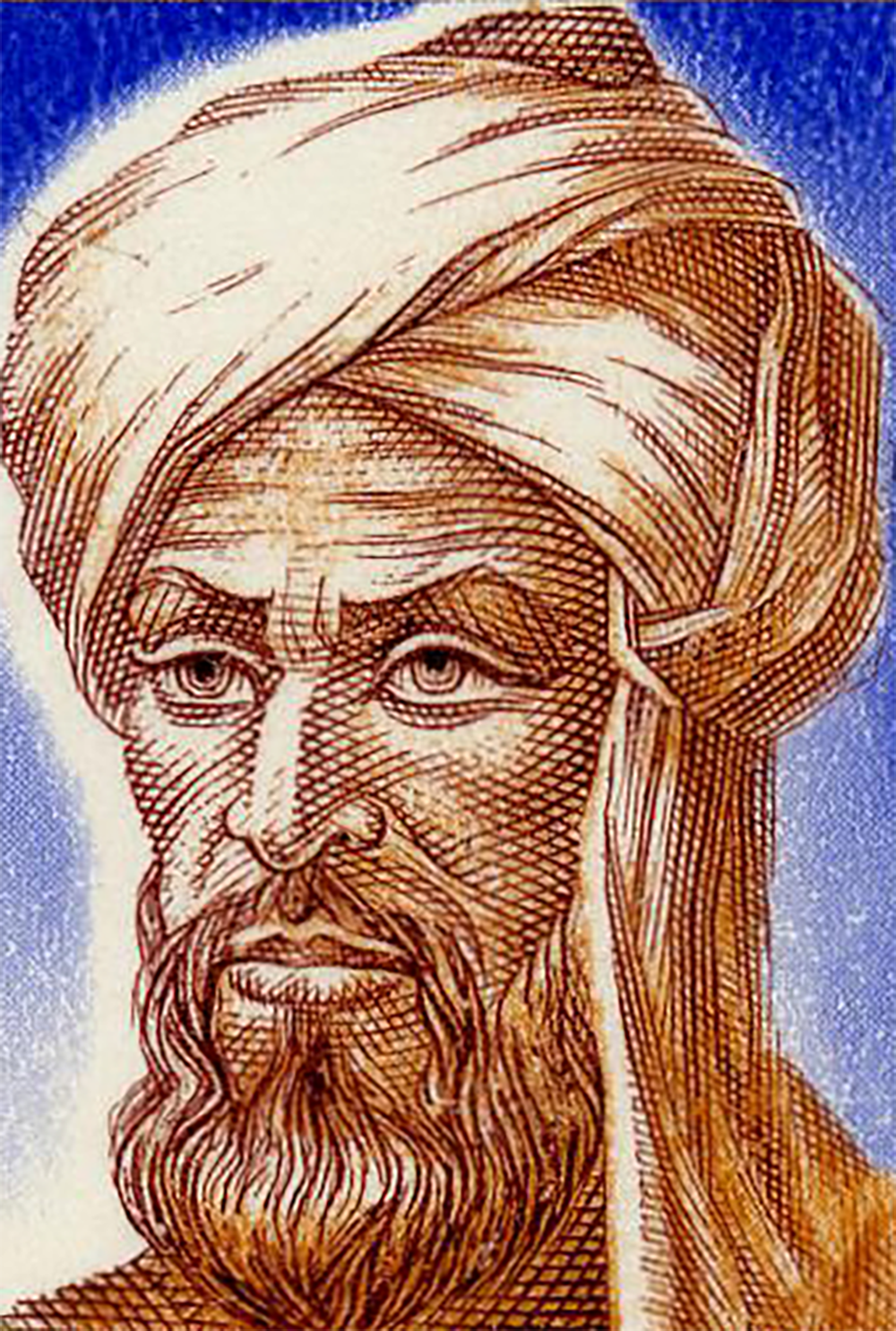

Algebra

Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (780-850)

Algebra, a concept in mathematics that uses letters and symbols to represent numbers and solve equations, is the main component of any technological or engineering feat, unbeknownst to many, and is, in fact, a contribution of Islam’s Golden Age. This invaluable contribution to the study of mathematics was made by renowned Persian scientist Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (780-850), regarded as the cornerstone of the sciences.

Algebra comes from Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi’s famous 9th-century treatise “Kitab al-Jabr Wa l-Mugabala”, which roughly translates to “The Book of Reasoning and Balancing.” Built on the roots of Greek and Hindu systems, the new algebraic order was a unifying system for rational numbers, irrational numbers and geometrical magnitudes.

The term “algebra” originates from the Arabic phrase “al-jabr,” signifying the “reunion of broken parts. Additionally, he was the first to introduce the concept of raising a number to a power. A British Arabist translated his work into what is now known as The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing. Following the translation of his book, he was referred to as Algoritmi, which is the root of the modern term “algorithm.”

These equations were devised to simplify life, particularly for calculations mandated by Islam, such as Zakat, inheritance division or land distribution, and salary distribution. Given the lack of 21st-century tools like calculators and computers, there was a need for efficient, accurate, and quick mathematical equations to assist with complex or lengthy calculations. The introduction of this concept expanded the scope of mathematics. Algebra has played a crucial role in the construction of nearly everything in the following centuries, from towering skyscrapers to computer science.

Hospital

Abu Bakr al-Razi (865-?) & Harun Al-Rashid (?-809)

The inception of hospitals as we understand them today can be traced back to the Islamic world in the 9th century. The first such institutions were established in Baghdad by Muslim physicians such as Abu Bakr al-Razi and Harun Al-Rashid, offering free healthcare to anyone in need irrespective of their societal standing, a practice rooted in the Muslim tradition of providing care for all who are ill.

The founding of the Ahmad ibn Tulun Hospital in 872 in Cairo was a significant event, as it was among the first fully operational hospitals and served as a model for the modern hospitals we see today. This model of healthcare was then propagated throughout the Muslim world. These Muslim hospitals were renowned for their hygiene and patient-centric approach and were staffed by highly skilled physicians and nurses.

These hospitals served multiple purposes, acting as treatment centres, recovery wards, and even retirement homes. Numerous similar medical facilities were established across the expansive Islamic Empire, known as “Bimaristan” or “Maristan”, terms derived from the Persian words for “ill” and “place”.

These institutions featured impressive lecture halls where medical students could learn from the seasoned doctors of the era. While they may not have met the standards we see today, these places served as the inspiration for the medical centres we now see around the world.

University

Fatima al-Firhi (800-880)

Many professions today, from archaeologists and researchers to doctors and engineers, require a university degree to be recognized and qualified in their fields. However, few people know that universities that award degrees are a legacy of the Islamic Golden Age.

The first university in the world that granted degrees was founded by a young princess named Fatima al-Firhi (800-880) in Fez, Morocco, in 859. She was joined by her sister Miriam, who built a mosque next to the university. The al-Qarawiyyin Mosque and University complex is still functioning today after almost 1,200 years. It is a testament to the Islamic tradition of learning and the legacy of the al-Firhi sisters, who have inspired young women worldwide.

Before this institution was founded, mosques also served as places of learning where people studied the Quran, fiqh (jurisprudence) and ahadith. Although Oxford and Cambridge are very old universities, dating back to the 13th Century, even older ones from the early Islamic era have endured until today. These include Al-Azhar University in Cairo, and the institution Fatima Al-Fihri established, known as Al-Qarawiyin.

Fatima Al-Fihri and her sister Mariam inherited a large fortune from their father and brother, which they used to start projects that would benefit the people of Fez, Morocco. They were concerned about the community and felt obliged to ensure that others could also attain the same high level of education they had been blessed with. Mariam built the monumental Al-Andalus Mosque in 859 AD, which was quickly followed by Fatima founding the Al-Qawariyin Mosque. The latter was so large that it was able to host a university within its walls.

There was no tuition fee; students lived on campus for free and got allowances for food and lodging. The university became so popular that applicants had to take Arabic, Quran and general sciences exams to get admitted. The curriculum was wide-ranging from religion, medicine and astronomy, with a strong emphasis on the natural sciences. Fatima Al-Fihri died in 880 AD, but her legacy lives on in her institution and the many other universities that followed her example worldwide.

Seeking knowledge is highly valued in Islam. The first word revealed to the Prophet Muhammed PBUH in the Quran was Iqra, meaning to “read.”

Flying Machine

Abbas ibn Firnas (810-887)

It’s astonishing that the inaugural human flight took place more than six centuries before Leonardo da Vinci’s aerial ventures and well over a millennium preceding the historic flight of the Wright brothers. This aviation journey commenced in the year 810 with the birth of Abbas Ibn Firnas in Malaga, Spain. Beyond his roles as a scientist, he also held titles as an inventor, poet, philosopher, alchemist, and astrologer.

Ibn Firnas notably set himself apart by designing a winged apparatus resembling a bird’s costume. One of his most celebrated experiments, conducted near Cordoba in Spain, saw him ascend from a tower and successfully achieve controlled flight for a brief duration before safely descending. However, he did sustain a partial back injury in the process.

Optics

Ibn Al-Haitham (965-1040)

Hassani underscores that the Muslim world has been the source of some of the most significant advancements in the study of optics. During the early 11th century, the Muslim physicist Ibn al-Haytham, recognized as Alhazen in the Western world, made groundbreaking contributions to this field. His pioneering research on light and vision paved the way for innovations like eyeglasses and lenses and challenged and reshaped established beliefs.

His magnum opus, the seven-volume “Kitab Al Manazer,” dared to challenge the prevailing theories of his era, most notably by proposing a revolutionary concept. Ibn al-Haytham argued that the human eye perceives objects by capturing the light reflecting off them, a theory contradicting the widely accepted notion that eyes emit light. This influential work, “Kitab al-Manazir,” has retained its status as one of the most influential treatises on optics throughout history.

Furthermore, during a house arrest imposed by the Fatimid ruler Al-Hakim, Ibn al-Haytham conducted pivotal investigations into optics fundamentals. One of his notable discoveries pertained to the pinhole camera. This revelation demonstrated that when a small aperture is created within a lightproof enclosure, it allows external light to pass through the aperture, projecting remarkably clear images onto the opposite wall. This pioneering revelation laid the essential groundwork for developing the modern camera as we know it today.

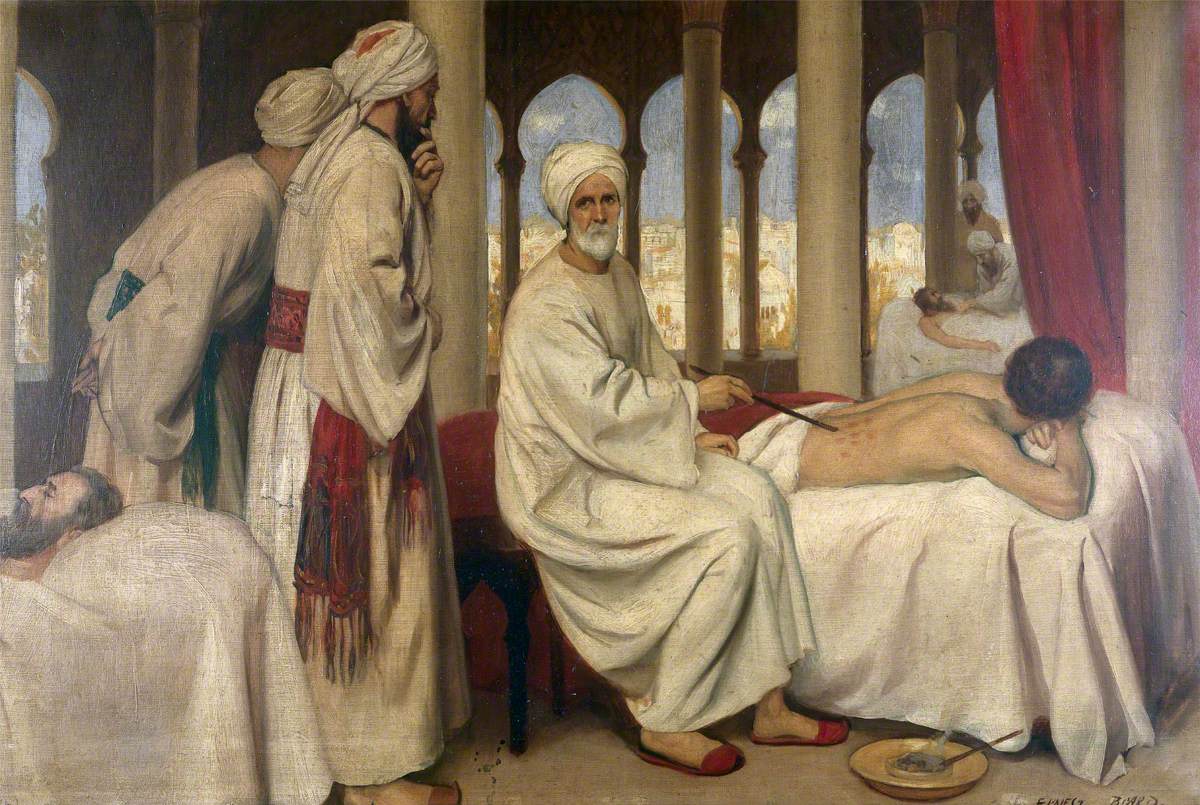

Surgery

Al Zahrawi (936-1013)

In the early 10th century, the esteemed physician Al-Zahrawi, also known as Albucasis, left an indelible mark on medicine by authoring a monumental 1,500-page illustrated encyclopedia on surgery. This magnum opus emerged around the year 1,000 and was a venerable medical reference throughout Europe for an astonishing half a millennium. Al-Zahrawi’s groundbreaking contributions to the field of surgery were nothing short of revolutionary, ushering in a new era of medical knowledge and practice.

Among the many revolutionary discoveries attributed to Al-Zahrawi, one noteworthy innovation was using dissolvable catgut to stitch wounds. Before his revelation, sutures used in surgical procedures necessitated a second surgery for their removal, often adding complexity and risk to the healing process. This single invention drastically improved the safety and efficiency of surgical interventions, ultimately changing the course of medical history.

Furthermore, historical accounts credit Al-Zahrawi with performing the first documented cesarean section, which remains essential in contemporary obstetrics. The legacy of Al-Zahrawi extends far beyond his groundbreaking inventions. Alongside other accomplished Muslim physicians, introducing new techniques and inventing surgical instruments that remain indispensable to this day. Among the instruments still widely used are scalpels, forceps, and surgical scissors, all of which can trace their origins back to the ingenuity of Al-Zahrawi and his contemporaries. His expertise and pioneering spirit continue to be an inspiration to medical professionals and researchers worldwide.

The Crank

Al Jazari (1136-1206)

The evolution of modern automatics owes a significant debt to the brilliant engineering marvels originating from the Muslim world. Among these groundbreaking innovations, the revolutionary crank-connecting rod system stands as a testament to the extraordinary ingenuity of Muslim engineers. This ingenious mechanism, capable of converting rotary motion into linear motion, has played a pivotal role in enabling the effortless lifting of heavy objects. Its impact reverberates through history, influencing many applications and shaping the fabric of our contemporary lives.

At the heart of this transformative technology was Al-Jazari, a visionary Muslim engineer whose brilliance illuminated the 12th century. Credited with the discovery and application of the crank-connecting rod system, Al-Jazari’s ingenuity opened new horizons for machinery. This innovative system simplified the process of lifting heavy loads and laid the foundation for many inventions that continue to define our modern world.

The global diffusion of the crank-connecting rod system marked a watershed moment in the progression of human innovation. Its applications are as diverse as they are impactful, from the unassuming bicycle, a beloved mode of transportation for millions, to the powerful internal combustion engine that fuels the vehicular marvels of the contemporary age. Beyond transportation, this ingenious mechanism has found its way into various sectors, enhancing manufacturing processes, powering industrial machinery, and even enabling the development of sophisticated robotic systems.

Al-Jazari’s legacy serves as a poignant reminder of the profound contributions made by Muslim engineers to the tapestry of human knowledge. His pioneering work not only transformed the mechanics of lifting but also ignited a chain reaction of advancements, reshaping industries and improving the quality of life for people around the globe. The ripple effect of his innovation continues to inspire generations of engineers, emphasizing the enduring importance of acknowledging and celebrating the diverse origins of our technological heritage.

The Windmill

Pīrūz Nahāvandi (600-644)

The arrival of windmills in 12th-century Europe is often attributed to the Crusaders, marking a pivotal historical moment. However, the origins of this transformative technology reach back much further, finding their roots in the ingenuity of a Persian innovator. This tale unfolds against the backdrop of early Islamic civilization during the rule of Umar Ibn al Khattab (RA) around 634.

At the heart of this story is a visionary Persian engineer who approached Caliph Umar (RA) with an audacious proposal: constructing a mill powered entirely by the wind. Captivated by the idea of harnessing nature’s energy for practical applications, Umar (RA) enthusiastically commissioned the construction of this groundbreaking wind-driven mill.

This event marked the dawn of wind power utilization in the Islamic world. The innovative windmills found their first applications in Seistan, a region vividly described by the geographer Al-Masudi in the tenth century as a “country of wind and sand.” Al-Masudi marvelled at the ingenious use of wind energy, particularly in driving pumps that irrigated gardens, showcasing the remarkable potential of this technology.

The historical evolution of windmills serves as a testament to the rich exchange of ideas and technologies among diverse civilizations. From the vast deserts of the Arab lands to the rolling hills of Central Asia, windmills became symbols of human adaptability and ingenuity. They seamlessly integrated into local environments, fulfilling crucial roles such as drawing water and grinding corn, thus significantly enhancing agricultural practices and improving the quality of life for communities.

Modern Chemistry

Jabir ibn Hayyan (721-815)

In the flourishing intellectual environment of the Islamic Golden Age, around the year 800, alchemy underwent a transformative evolution, transitioning into the rigorous discipline of chemistry thanks to the pioneering efforts of Islam’s eminent scientist, Jabir ibn Hayyan. His profound contributions laid the foundation for the modern science of chemistry but also introduced numerous fundamental procedures and equipment that continue to shape scientific practices today.

Among his pioneering inventions were distillation, a process critical for separating components based on their different boiling points, and evaporation, used for concentrating solutions by removing the solvent. He mastered crystallization, the art of forming crystals from a solution and developed techniques for purification, ensuring the isolation of specific substances from complex mixtures. Ibn Hayyan’s innovative mind also gave rise to filtration methods, enabling the separation of solids from liquids and oxidization processes, which involve the combination of substances with oxygen.

Furthermore, Jabir ibn Hayyan’s scientific inquiries led to the discovery of crucial chemical compounds. He was instrumental in identifying and understanding the properties of sulphuric acid and nitric acid, two fundamental acids that have significant applications in various industrial and laboratory processes even today.

Jabir ibn Hayyan’s pioneering work in chemistry was not merely a collection of isolated discoveries; it embodied the principles of systematic investigation and experimentation. His meticulous observations and methodical approach to scientific exploration make him revered.

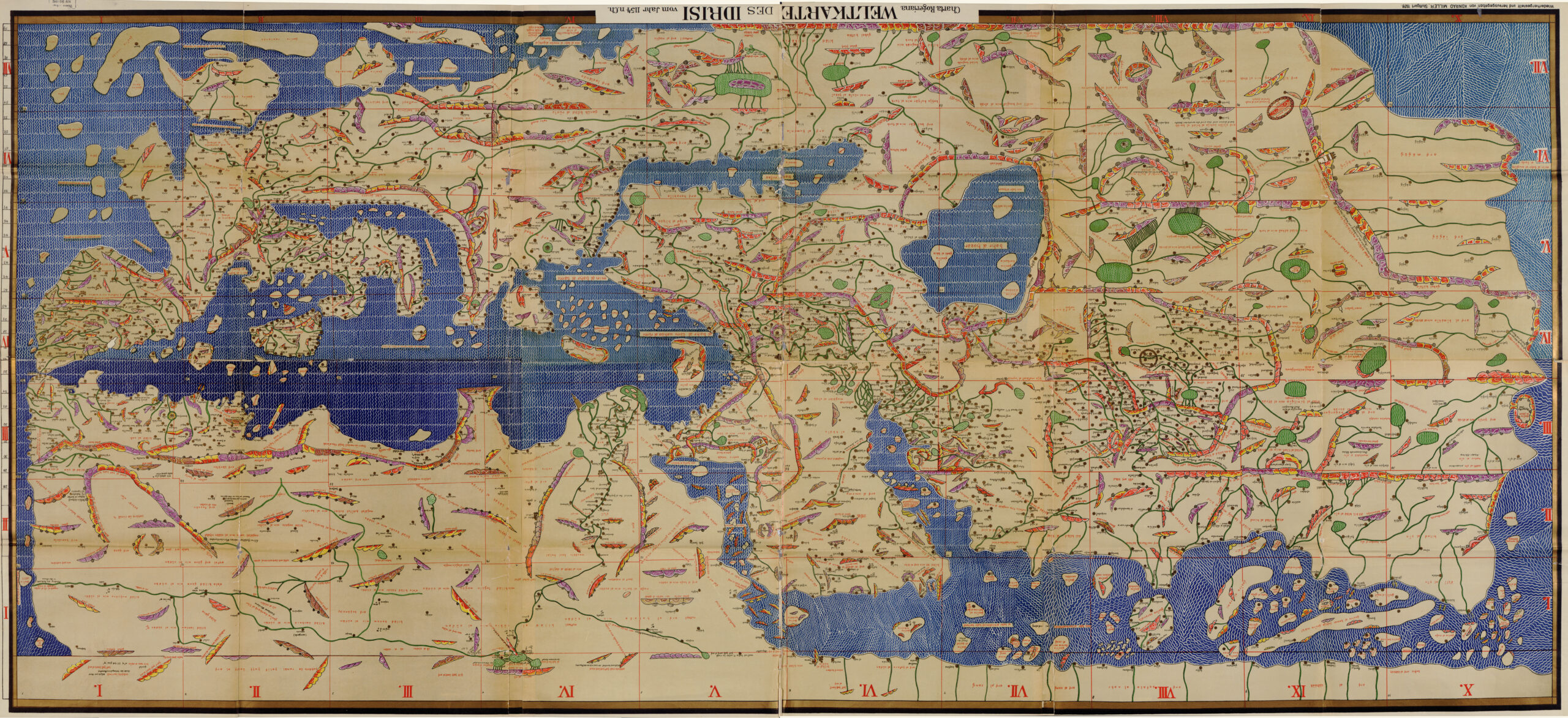

Tabula Rogeriana

Al-Idrisi (1100-1165)

The Tabula Rogeriana, a masterpiece of medieval cartography, was crafted in 1154 by the Arab geographer Al-Idrisi under the patronage of King Roger II of Sicily. This circular world map, part of Al-Idrisi’s comprehensive geographical compendium, exhibited a unique south-up orientation, deviating from the prevailing north-centric maps of the time. The silver disk featured an intricate grid system and division into climate zones, showcasing advanced cartographic techniques.

Al-Idrisi’s map synthesised knowledge from Greek, Roman, and Islamic sources, offering a nuanced and inclusive representation of the known world. It meticulously depicted rivers, mountains, and major cities, contributing to its accuracy and significance. Despite the original’s loss, subsequent copies and adaptations, such as the renowned 16th-century Ptolemaic map by Ottoman cartographer Piri Reis, underscored the enduring influence of the Tabula Rogeriana.

Beyond its cartographic innovation, the Tabula Rogeriana was a cultural bridge, facilitating knowledge exchange between diverse traditions. It remains a testament to Al-Idrisi’s ingenuity and the dynamic interplay of ideas during the medieval period, leaving an indelible mark on the history of cartography and cross-cultural intellectual exchange.

Beyond their individual achievements, Muslim scholars fostered an environment of intellectual curiosity, openness to diverse ideas, and a commitment to rigorous inquiry. For instance, the House of Wisdom in Baghdad became a vibrant centre for translation, where texts from various cultures were translated into Arabic, preserving and disseminating knowledge. This cultural exchange facilitated the transmission of classical Greek, Roman, and Indian knowledge, influencing the Renaissance in Europe.

In essence, the contributions of Muslim scholars were not confined to a specific time or region but reverberated across centuries and continents, influencing the trajectory of human progress. Their intellectual endeavours advanced knowledge in their respective fields and laid the groundwork for the Renaissance and the Scientific Revolution. Today, as we delve into the annals of history, it is imperative to acknowledge and celebrate the profound impact of Muslim scholars whose intellectual legacies continue to shape our understanding of the world.

Toothbrush

As per Hassani’s account, Prophet Mohammed played a significant role in the early adoption of the first toothbrush around the year 600. He utilized a twig from the Meswak tree to maintain oral hygiene by cleaning his teeth and refreshing his breath. Today, contemporary toothpaste contains ingredients akin to Meswak.

Music

According to Hassani, Muslim musicians have had a significant and lasting influence on Europe. This musical exchange can be traced back to the era of Charlemagne, who sought to rival the music of Baghdad and Cordoba. Among Europe’s numerous musical contributions from the Middle East are instruments like the lute and the Rahab, which can be considered an ancestor of the violin. Additionally, it’s believed that modern musical scales have their roots in the Arabic alphabet.

Gardens

Medieval Europe’s concept of gardens primarily revolved around their utilitarian purpose, serving as practical spaces for cultivating food and medicinal herbs. It wasn’t until the influence of Arab culture began to permeate the continent that gardens took on a new dimension, transforming into serene havens for beauty and contemplation. This cultural shift was initially introduced to Muslim Spain during the 11th century, marking the beginning of a significant horticultural transformation.

The infusion of Arab gardening traditions into Europe brought about an array of previously unknown flora in these regions. The carnation and the tulip stand out among the many botanical treasures that graced European gardens due to this exchange. These flowers, initially cultivated in the lush and meticulously tended gardens of the Muslim world, added vibrant colours and fragrant beauty to European landscapes, forever altering their gardens’ aesthetic and sensory experience.

Coffee

Coffee, now a global beverage, originated in Yemen in the 9th century and was initially consumed by Sufi monks for late-night devotion. Introduced to Cairo by students, it spread through the Islamic world, reaching Turkey in the 13th century and Europe in the 16th century. Coffeehouses, integral to Islamic society, emerged, becoming hubs for intellectuals. The Ethiopian origin story involves a Muslim named Khalid discovering the energizing properties of coffee berries. The Arabic qahwa evolved into Turkish kahve, Italian caffe, and English coffee. Coffee faced initial European suspicion but gained Pope Clement VIII’s approval in 1600. Today, it’s the world’s second-most traded commodity.